| Conspiracy theories – why do people believe in them? | |||

|

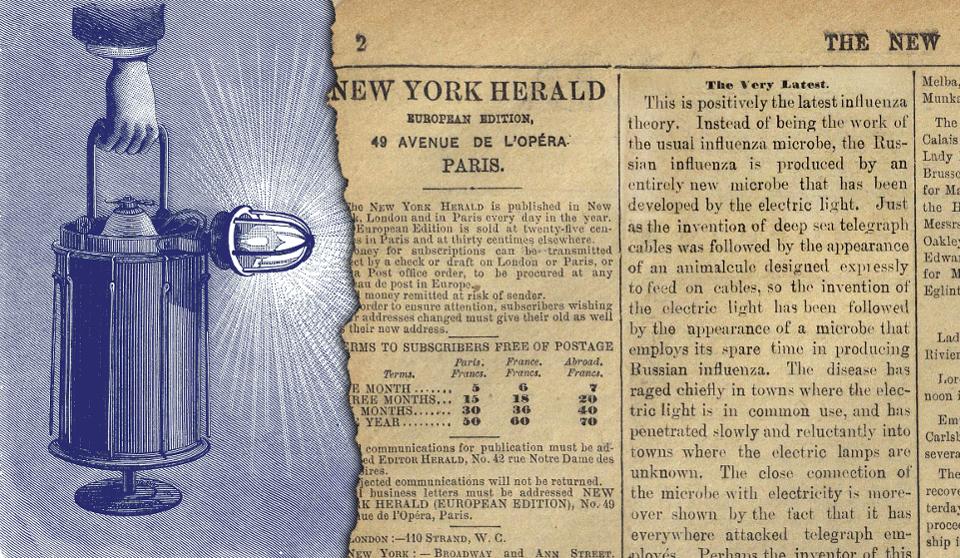

Mrs Elizabeth Carlill became ill, despite having inhaled the smoke for at least two weeks, and requested the promised compensation. The Company refused to pay, saying that it was only an advertisement and so not to be taken seriously. Their advertised claim was in their words ‘a mere puff’ and so couldn’t give rise to an enforceable contract. The Court of Appeal unanimously decided otherwise. I have to say that it’s one of the case names you tend not to forget! This though was just one of the many dubious claims put forward as sure-fire remedies for a plague which was to kill more than a million people around the globe during the first four months after its spread from Russia. It was a time when travel had taken off and so diseases were no longer mainly confined to their original location. Shades of today? Castor oil was a treatment pushed by at least one newspaper, and others included an electric battery (which promised to improve eyesight as well). Some doctors promoted the idea that drinking brandy and eating oysters was the key to staving off infection. At a time when the microbe theory of disease was starting to replace the previous miasma theory – that disease was caused by bad air from rotting matter - another doctor claimed to have found the microbe which was to blame. The source of these microbes, Dr. Gentry claimed, was stardust passing through the Earth’s atmosphere at regular 16 to 17 year intervals. Other physicians soberly rejected Dr. Gentry’s idea - preferring instead to blame volcanic dust, bird migrations or other equally bizarre causes. What though is an obvious parallel with the present day distrust of 5G masts is referred to in an article on January 31, 1890, in the New York Herald. It suggested that it was a microbe developed by the electric light which was responsible for the global influenza outbreak. After all, “the disease has raged chiefly in towns where the electric light is in common use,” the article noted, and “has penetrated slowly and reluctantly in towns where the electric lamps are unknown” Do I hear ‘but correlation is not causation’? An idea which itself apparently dates from 1880.

But there is in all of us a wish to know what to blame for what afflicts us and so inevitably there are those, like the Carbolic Smoke Ball Company, who will try to make money out of our ignorance. But what we call ‘Conspiracy theorists’ or ‘Truthers’, as they call themselves, are often in a different category. They genuinely believe their explanations and are not making money out of their beliefs. So why do people actually believe in conspiracy theories, theories which have no foundation and which are built on connections which are simply pure conjecture? A study has been carried out recently by academics, Stephen Murphy and Tim Hill. In an interview with The Irish Times, they explained that they had immersed themselves in the conspiracy theory community, attending their events, carrying out informal interviews and observing their social media use at home. “Any crisis, pandemic or otherwise, is fertile ground for conspiracy theories because people search for easy explanations for something that appears unmanageable,” Murphy and Hill say. “Conspiracy theories allow people to believe there is a hidden structure to the world. They are fundamentally reassuring – a comforting ideological fantasy – since they propose that someone, somewhere, is in control, no matter how malevolent they may be.”. The research suggests a lot of us are susceptible to wishful thinking, and those who aren’t may be insulated by privilege. Many of the participants in their study live in de-industrialised parts of England “and feel let down by the government which did not do enough to protect their jobs, and feel that the managerial class betrayed them”. “They have also seen their own and their children’s living standards decline while the rich grow richer, profiting from their misery. For them the idea, for example, that Bill Gates engineered the pandemic, to fuel demand for a vaccine from which Gates will personally profit, helps explain the deep patterns of prejudice, lack of recognition, and economic inequality they feel around them.” Asked whether social media is accelerating the spread of conspiracy theories, they replied: “To explain why ordinary people on Facebook are doing this, it is important to understand that conspiracy theory communities including anti-5G groups are intensively competitive. A person’s status in the community is determined by building new and unmade causal explanations to events that occur in the world. This constant uncovering of previously unknown connections is expressed through a common cultural trope, seen on television and in films, the ‘heroic detective’. Those that dare to go further down the rabbit hole, uncovering additional links to explain obscure historical events and current world events, are celebrated within the community as heroic seekers of the truth. For people who are largely on the margins of society, this identity and prestige provides invaluable social value. The people who champion conspiracy theories are often dismissed as delusional, paranoid or crazy. These stereotypes motivate psychological research that explains these beliefs in terms of psychological characteristics or cognitive errors. “While this desire to seek underlying psychological causes is understandable, it doesn’t provide a complete picture of why some conspiracy theories resonate with particular groups of people at specific moments in time. In this way, conspiracy theories can be treated like any other cultural narrative, or what sociologists sometimes call ‘a deep story’, in which the facts of a story needn’t be true - what matters is that the story both feels true, and also addresses particular anxieties, sadness or anger. Conspiracy theorists are in their view heroic seekers of the truth who contest the orthodoxies ‘imposed’ by authority.” What the researchers are saying is that these people are believers in a secular religion. And we know how susceptible superstition is to rational argument. That conspiracy theorists exist, however, might be dismissed as an irrelevance if they were not being used by others to gain and retain power. In the USA, conservatively weighted courts are making decisions on the lockdown regulations based on the rejection of scientific reality because it doesn’t fit with their right wing political views. And then we have various world leaders also disinclined to admit what is obviously (to us) the truth. Rejecting global warming as a threat to their extreme capitalist and nationalist agendas, there are numerous global leaders such as Trump, with his gossamer light relationship to the truth. So are they too, in their own minds, heroic seekers of truth? Or is there perhaps a different explanation? Might it be that the views they express deliberately chime with the ignorant and disadvantaged amongst their electorates and so help them gain power? Even if the ordinary conspiracy theorist in his underpants really is convinced that the world is out to get him, I doubt that those wielding real power have the same fears or concerns about the Elders of Sion, the Illuminati or the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, or even share the profound ignorance found amongst a large part of the population. Theirs is a rather more cynical view. And they of course are even more dangerous to the rest of us than those holding banners saying: ‘Give me Covid or Death’. If only. Paul Buckingham 18 May 2020 |

|||

|

|