| The Perils of Perception | ||

|

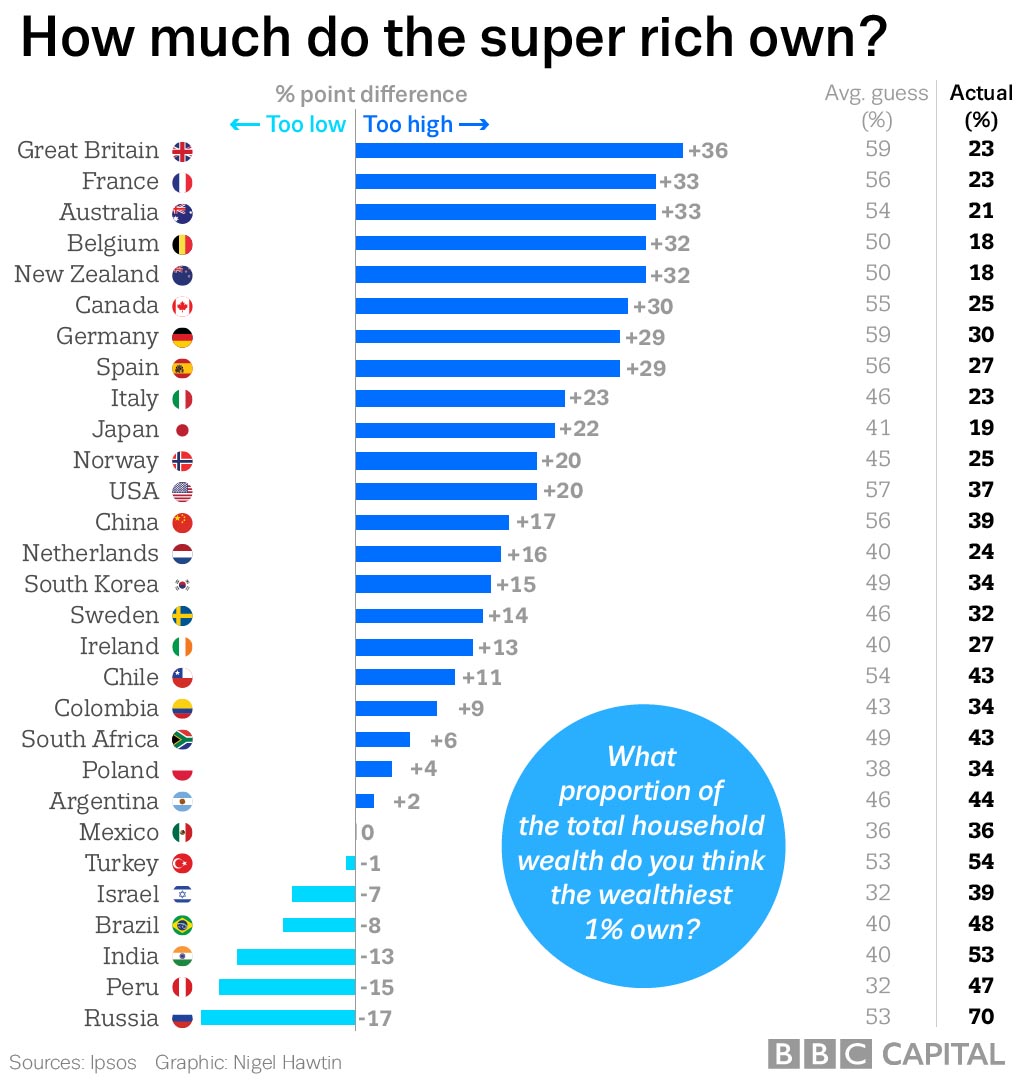

We want to believe that we are rational beings, that we base our decisions on logic. It is generally accepted that this ability distinguishes us from other animals. And it is true that we have made a lot of progress in the scientific sphere. We have developed many theories to explain our world and then we test them with experiments. In light of the results we modify our theories in order to arrive at an understanding of how at least a part of the world works. Someone in the scientific community who did not follow this process would be ignored and, therefore, as a system, it works quite well. In principle this approach - theory, experiments, modification of the theory and ... repeat - can be used not only in science but also in other spheres of life. The difficulty, however, is that we have preconceived ideas of how the political world works and how it should work. This difficulty exists in the fact that our prejudices have the status of a religion (in the broadest sense) and therefore prevent us from wanting to challenge them or to believe the results of each "experiment" or detailed investigation of what happened in the past that would indicate something contrary to our prejudices. We say that everyone has the right to believe in what he wants to believe and therefore there is no real motivation, as in science, to correct our mistakes. We admire those who stick to their beliefs or their principles and criticize those who are without principles. A fiery Brexiteer yesterday criticized one of his colleagues saying: "He can write all his principles on the back of a postage stamp". It is pride in the belief that our principles should be a constant in our lives that prevents us from being the rational creatures we claim to be. But why should our principles not be subject to review? Having seen the injustice that existed in society in the eighteenth century in France, the revolutionaries decided, as a principle, an article of faith, that equality was the key requirement for a good life. In Russia, the communists came to the same conclusion after a long history of excess among the aristocracy. In the end, however, this article of faith, a part of 'Scientific Socialism', was abandoned, not because its supporters saw the results of their experiment and admitted their mistake, but because the resulting economy, based on equality, was simply no longer capable of functioning, even in a modified form that allowed some inequality. And it did not work because an economy depends on the wishes and choices we all make in our lives. These desires and these choices emerge from our psychology in all its complexity and not from an oversimplified concept, an article of faith, that of equality. I am not convinced, however, that our politicians are currently able to change their approach. And I do not think that the people have the necessary knowledge of what is happening in the world to ask for the changes required to make it all work better. But I do now have at least the impression that after more than a century of "social sciences", we are starting to do research in a more scientific way about the human condition. And having these data can, perhaps, one day feed our political life. What caught my attention was a book written by Bobby Duffy, former head of Ipsos Mori, the survey company. There is also an academic study on the perception of inequality, published in August 2017. The authors of the study remind us that for many years there has been a belief in academic circles that inequality was a very important issue in the political world, whether under a democratic or autocratic regime. They say that in a democracy the poor can vote to impose taxes on the rich. It is believed that the richer are the rich, the more the poor will be likely to vote to tax the rich to produce more generous social spending. Unequal democracies should therefore redistribute more than democracies that are more equal. In dictatorships, the greater the wealth gap, the more the poor can gain from overthrowing and expropriating the wealth of their rulers. Very unequal autocracies should therefore be more prone to revolution than less unequal ones. As a matter of self-protection, extreme inequality should discourage support for democracy among the rich. These arguments, from Aristotle to Marx, seem to be plausible. But it's not that simple. We can all think of obvious exceptions, such as America, and there is also the question about what it means to be rich? We live in a period when, according to statisticians, for the first time since the establishment of a reliable world statistical system, 1% of the richest people in the world have more than the rest of the population put together. One can imagine, as did Marx and the French revolutionaries, that the default position among the population is “I should be as rich as anyone else”. But according to the Ipsos Mori polls* and recent studies this is not the case. In fact we have a tolerance for fairly considerable inequality. Perhaps it is because, even that we now have statistical data capable of indicating when the system is unequal, even before the existence of these statistics, we knew that the inequality was widespread. Possibly through the millennia we learned to accept it as something fundamental in the world. Perhaps also because one day I could become richer than my neighbour. And now a reality check – as recorded by the pollsters, according to the general public, how much do the super-rich possess, this famous 1%? The answer is that we estimate that the super-rich own 45% of the wealth of the country. In fact, though the proportion of wealth that the super-rich actually possess varies from 18% for Belgium and New Zealand to 70% for Russia. The majority of countries are grouped around 35% of total wealth, a 10% deficit as compared to what we think they have! The estimate for Great Britain is that the super-rich have 59% of our assets, when in fact they have only a miserable 23%. Obviously they don’t make the effort! And what percentage of the wealth of the country are we willing to accept should be held by this legendary 1%? Apparently it is between 14% (Israel) and 33% (Brasilia). And so for example in England we think that they should have 20% against the actual 23% and the 59% we think that they have. There are even 5 countries where citizens would think that their rich are actually too poor, including Italy. But in almost every case the perception is that the rich are much richer than they are in reality and, for the most part, the reality is that their wealth does not diverge much from the ideal percentage as imagined by the public.* This type of extraordinary ignorance does not apply, however, only to wealth. According to Mr. Duffy's book, it is true in almost every part of political life. We consistently overestimate the rate of murder, the number of terrorist attempts or the number of migrants living here, to the number of people in absolute poverty. What does it mean? That creating a policy of redistribution based on received opinion is very dangerous. In fact, creating any policy based on unchecked mass opinion is very dangerous. We accept that democracy does not consist only in the freedom to vote, but in everything else that supports our democratic system: the rule of law, etc. To this should we not add education in the key social figures? Paul Buckingham November

2018

|

||

|

|